The Threat of Transformer Arises — Challenger Mamba (From SSM, HiPPO, S4 to Mamba)

Will upload before May.

#You may find the reproduce work here.

1 State Spaces Model

1.1 What is State Spaces

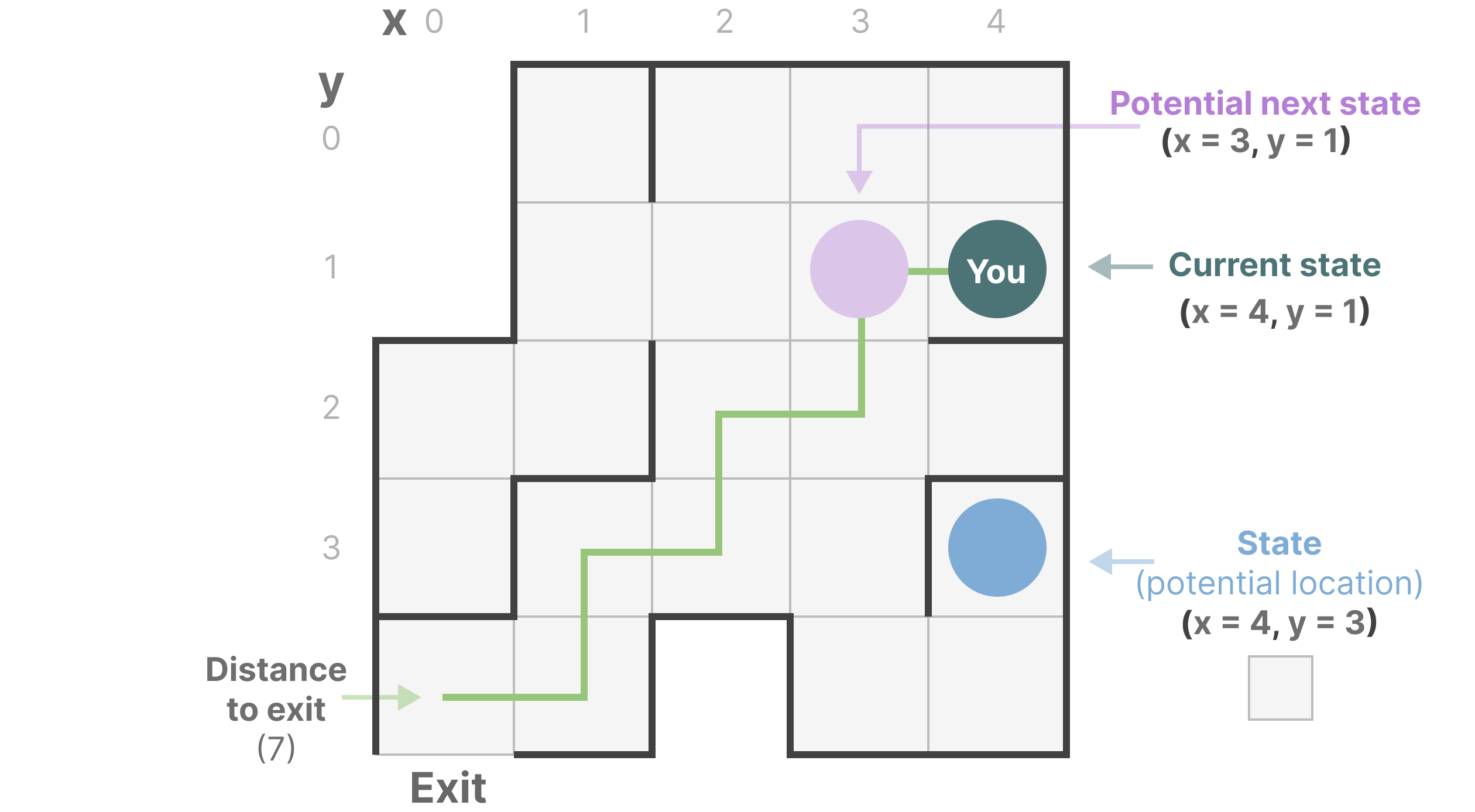

Imagine we are walking through a maze. Each small box in the diagram represents a position in the maze and contains some implicit information, such as how far you are from the exit.

The above maze can be simplified and modeled as a ‘state space representation’, where each small box displays:

- Your current location (current state)

- Where you can go next (possible future states)

- Which actions will take you to the next state (e.g., moving right or left)

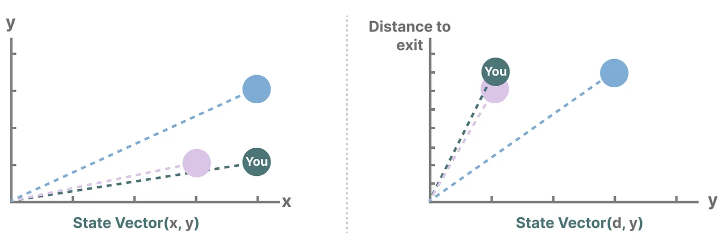

The variables describing the state (in our example, the X and Y coordinates and the distance to the exit) can be represented as ‘state vectors’.

1.2 What is State Spaces Models (SSM)

SSM (State Space Model) is a model used to describe these state representations and predict their next state based on certain inputs.

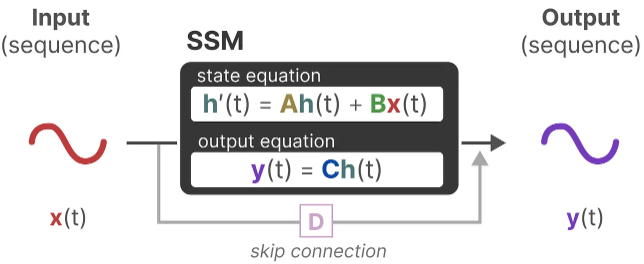

Generally, SSMs include the following components:

- Mapping input sequences x(t), such as moving left and down in the maze,

- To latent state representations h(t), such as the distance to the exit and x/y coordinates,

- And deriving predicted output sequences y(t), such as moving left again to reach the exit faster.

However, it does not use discrete sequences (like moving left once), but instead takes continuous sequences as inputs to predict output sequences.

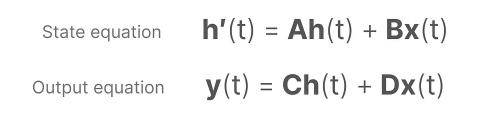

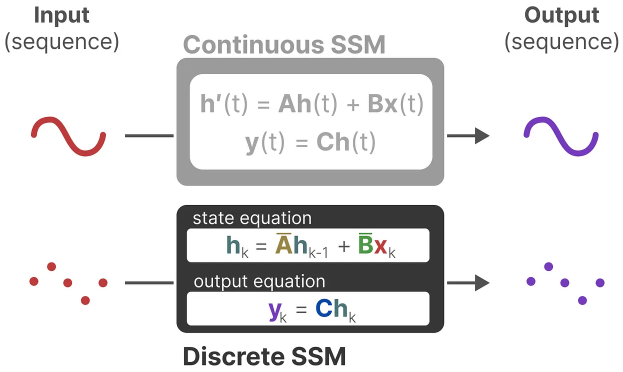

SSMs assume that dynamic systems, such as an object moving in 3D space, can be predicted from its state at time t through two equations.

By solving these equations, it is possible to predict the state of the system based on observed data (input sequences and previous states). Therefore, the above equations represent the core idea of the State Space Model (SSM).

1.3 State Equation and Output Equation

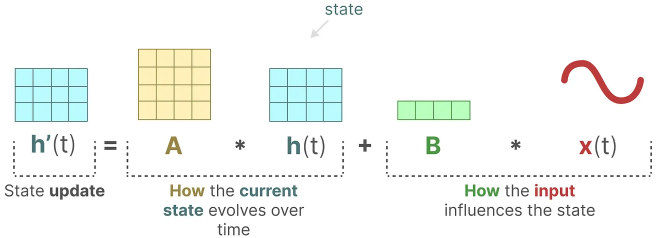

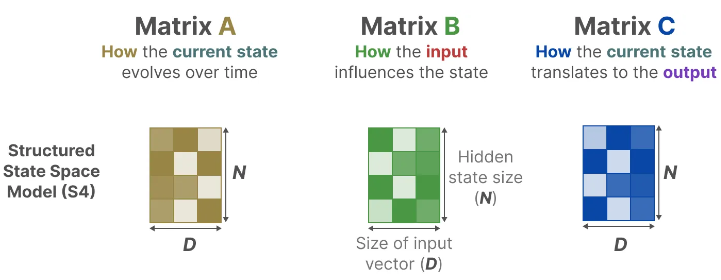

The state equation describes how the state changes (through matrix A) based on how the input influences the state (through matrix B).

As we saw before, h(t) refers to our latent state representation at any given time t, and x(t) refers to some input.

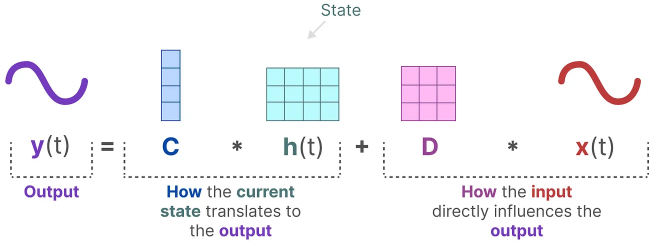

The output equation describes how the state is translated to the output (through matrix C) and how the input influences the output (through matrix D).

1.4 Fata Flow Detail

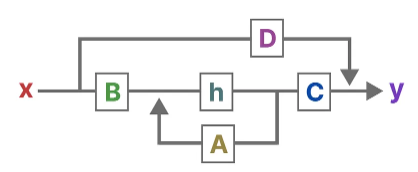

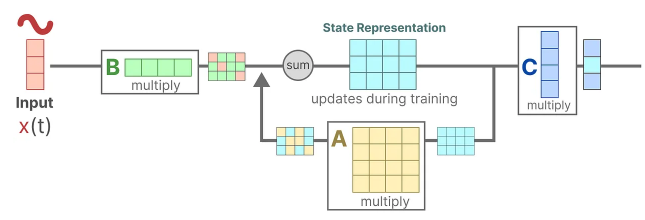

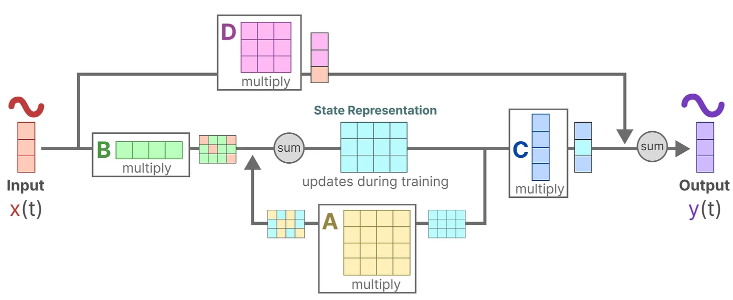

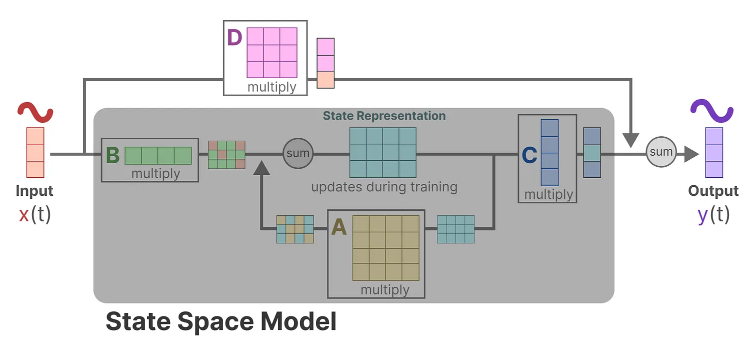

Visualizing above two equations gives us the following architecture:

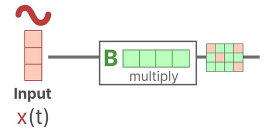

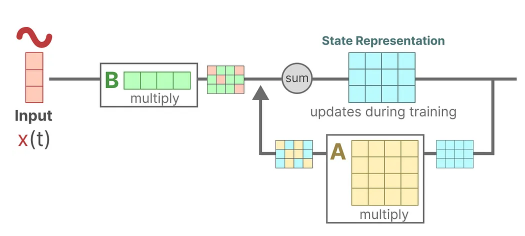

Assume we have some input signal x(t), this signal first gets multiplied by matrix B which describes how the inputs influence the system.

The updated state (akin to the hidden state of a neural network) is a latent space that contains the core “knowledge” of the environment. We multiply the state with matrix A which describes how all the internal states are connected as they represent the underlying dynamics of the system.

Matrix A is applied before creating the state representations and is updated after the state representation has been updated.

Then, we use matrix C to describe how the state can be translated to an output.

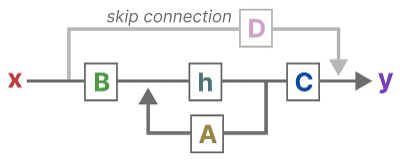

Finally, we can make use of matrix D to provide a direct signal from the input to the output. This is also often referred to as a skip-connection.

Since matrix D is similar to a skip-connection, the SSM is often regarded as the following without the skip-connection.

Going back to our simplified perspective, we can now focus on matrices A, B, and C as the core of the SSM.

We can update the original equations (and add some pretty colors) to signify the purpose of each matrix as we did before.

Together, these two equations aim to predict the state of a system from observed data. Since the input is expected to be continuous, the main representation of the SSM is a continuous-time representation.

2 From SSM to S4

Three-step upgrade from SSM to S4: discretized SSM, cyclic/convolutional representation, long sequence processing based on HiPPO

2.1 From a Continuous to a Discrete Signal

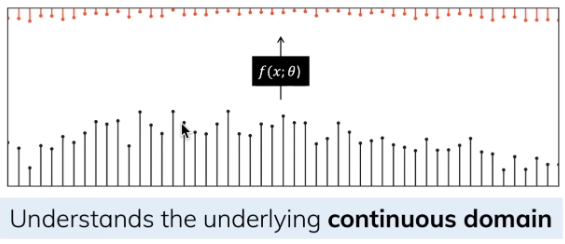

In addition to continuous inputs, discrete inputs (such as text sequences) are also commonly encountered. However, even when trained on discrete data, an SSM can still learn the underlying continuous information. This is because, for an SSM, a sequence is merely a sampling of a continuous signal, or in other words, the continuous signal model is a generalization of the discrete sequence model.

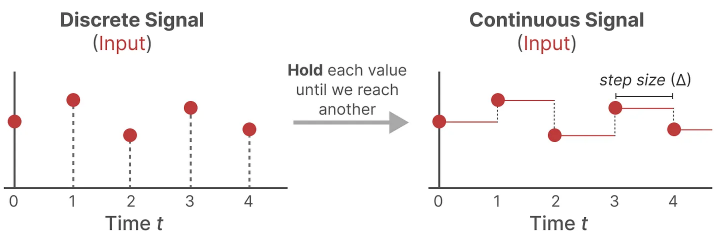

The Zero-order hold technique can be used to discretize the model, thus handling discrete signals.

- Initially, when a discrete signal is received, its value is maintained until a new discrete signal is received. This operation results in the creation of a continuous signal that the SSM can utilize.

The duration for which this value is held is represented by a new learnable parameter known as the step size (siz) — Δ, which signifies the phased hold (resolution) of the input.

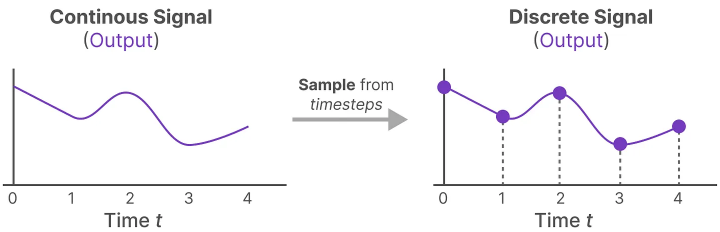

With the continuous input signal available, continuous outputs can be generated, and values are sampled based solely on the input’s time step size.

These sampled values become our discrete outputs, and for matrices A and B, the zero-order hold can be applied in the following way:

Discretized matrix A

\[\bar{A} = \exp(\Delta A)\]Discretized matrix B

\[\bar{B} = (\Delta A)^{-1} (\exp(\Delta A) - I) \cdot \Delta B\]They collectively enable us to transition from a continuous SSM to a discretized SSM represented by the formulas. The model no longer represents a function to function \(x(t) \rightarrow y(t)\), but rather a sequence to sequence \(x_k \rightarrow y_k\):

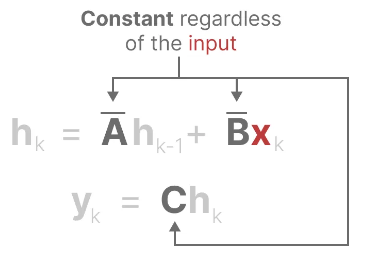

Here, matrices A and B now represent the discrete parameters of the model.

We use k instead of t to denote discrete time steps, making it clearer when we refer to continuous SSM versus discrete SSM.

Note: During training still maintain the continuous form of matrix A, not the discretized version. The continuous representation is discretized during the training process.

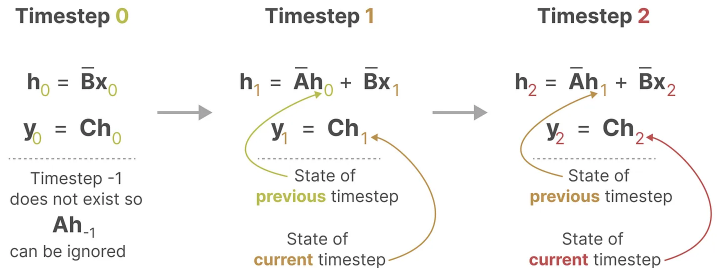

2.2 The Recurrent Representation

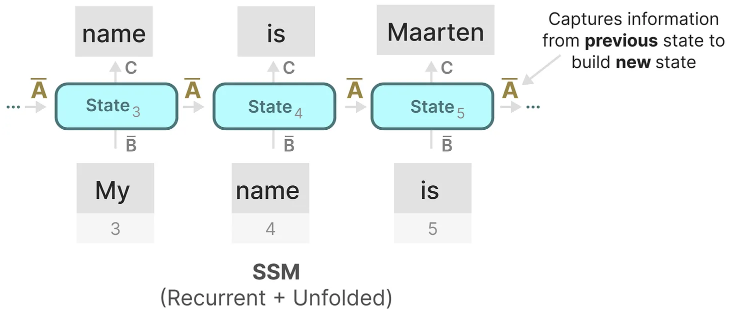

The discrete SSM allows the problem to be reformulated using discrete time steps. At each time step, we compute how the current input \((Bx_k)\) affects the previous state \((Ah_{k-1})\), and then calculate the predicted output \((Ch_k)\).

If we expand y2 we can get the following:

\(y_2 = Ch_2\) \(= C(Ah_1 + Bx_2)\) \(= C(A(Ah_0 + Bx_1) + Bx_2)\) \(= C(A(A \cdot Bx_0 + Bx_1) + Bx_2)\) \(= C(A \cdot A \cdot Bx_0 + A \cdot Bx_1 + Bx_2)\) \(= C \cdot A^2 \cdot Bx_0 + C \cdot A \cdot B \cdot x_1 + C \cdot Bx_2\)

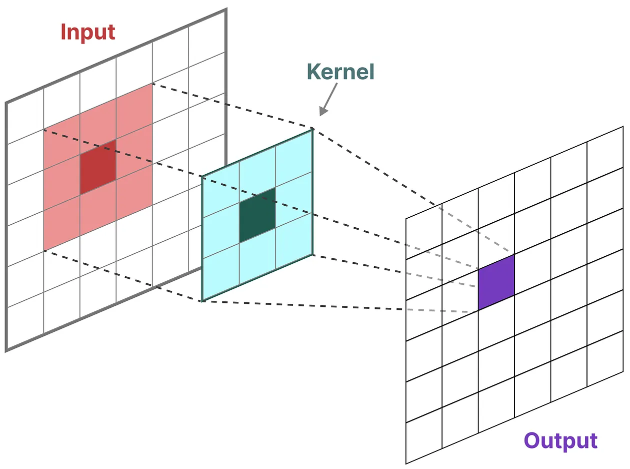

2.3 The Convolution Representation

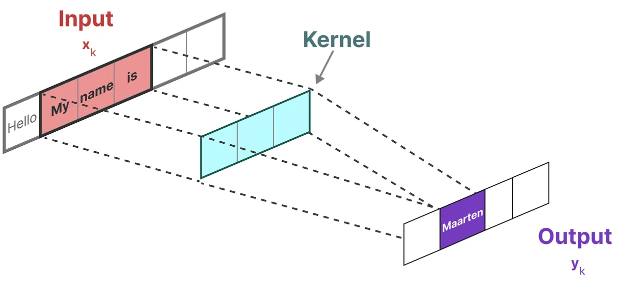

Another representation that we can use for SSMs is that of convolutions. Remember from classic image recognition tasks where we applied filters (kernels) to derive aggregate features:

Since we are dealing with text and not images, we need a 1-dimensional perspective instead:

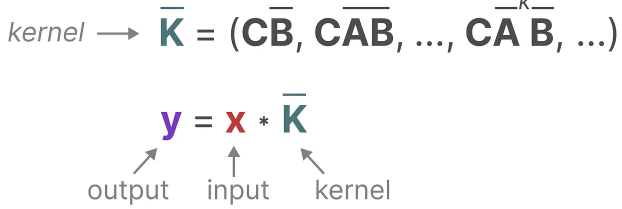

The kernel that we use to represent this “filter” is derived from the SSM formulation:

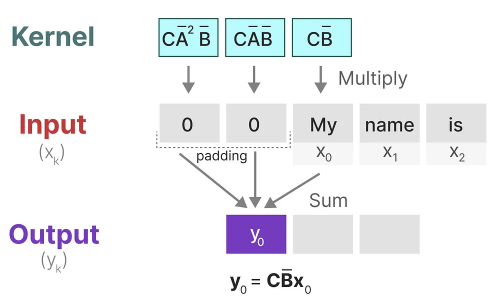

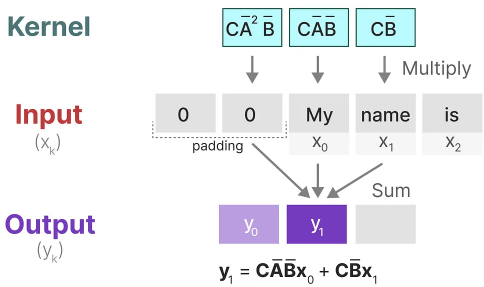

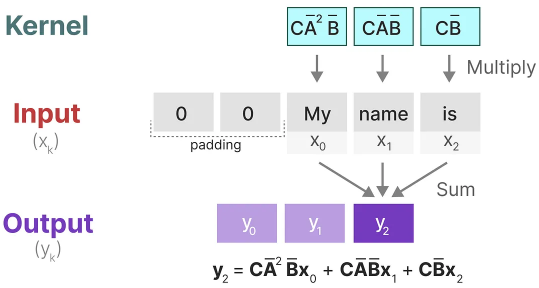

Let’s explore how this kernel works in practice. Like convolution, we can use our SSM kernel to go over each set of tokens and calculate the output:

This also illustrates the effect padding might have on the output. I changed the order of padding to improve the visualization but we often apply it at the end of a sentence.

In the next step, the kernel is moved once over to perform the next step in the calculation:

In the final step, we can see the full effect of the kernel:

A major benefit of representing the SSM as a convolution is that it can be trained in parallel like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). However, due to the fixed kernel size, their inference is not as fast and unbounded as RNNs.

If we separate the parameters and inputs of the formula, we get:

\[y_3 = \begin{pmatrix} CAAA & CAAB & CAB & CB \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x_0 \\ x_1 \\ x_2 \\ x_3 \end{pmatrix}\]Since the three discrete parameters A, B, and C are constants, we can pre-compute the left-hand side vector and save it as a convolution kernel. This provides us with a straightforward method to compute \(y\) at very high speeds using convolution, as shown in the following two equations:

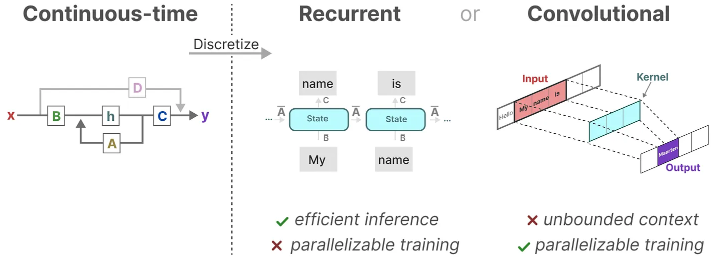

\[K = (CB \quad CAB \quad \dots \quad CA^kB)\] \[y = K \ast x\]2.4 Continuous, Recurrent, and Convolutional Representations

These three representations, continuous, recurrent, and convolutional all have different sets of advantages and disadvantages:

One of the main benefits of representing the SSM as a convolution is that it can be trained in parallel similar to convolutional neural networks (CNNs). However, due to the fixed size of the kernel, their inference is not as fast as that of RNNs.

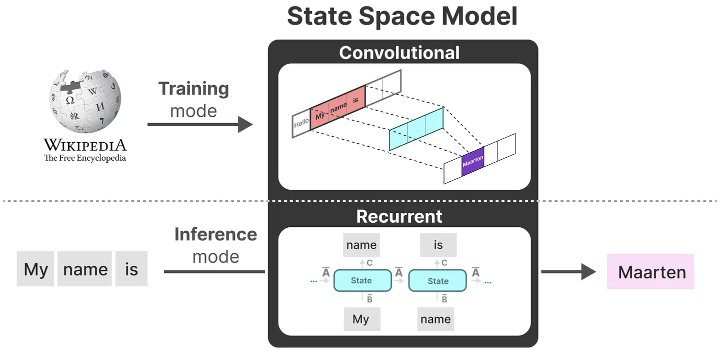

Interestingly, we can now use a recurrent SSM for efficient inference and a convolutional SSM for parallel training.

With these representations, we can use a clever trick: choose the representation based on the task. During training, we use the convolutional representation that can be parallelized, and during inference, we use the efficient recurrent representation:

This model is called the Linear State Space Layer (LSSL).

These representations share an important property, linear time-invariance (LTI). LTI dictates that the SSM parameters A, B, and C are fixed for all time steps. This means that for every token generated by the SSM, the matrices A, B, and C are the same.

In other words, no matter what sequence you provide to the SSM, the values of A, B, and C remain unchanged. We have a static representation that does not recognize content.

Before we explore how Mamba addresses this issue, let’s discuss the final piece of this puzzle: matrix A.

2.5 HiPPO, The solution to the long-distance dependency problem

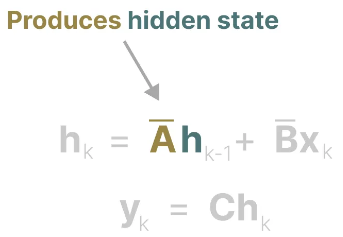

Matrix A can be considered one of the most crucial aspects of the SSM formula. As we have seen in the recurrent representation, it captures information about previous states to construct new states. \(h_k = \overline{A} h_{k-1} + \overline{B} x_k\), and when k = 5, then \(h_5 = \overline{A} h_{4} + \overline{B} x_5\).

In essence, matrix A produces the hidden state:

Since matrix A only remembers the previous few tokens and captures the differences between every token seen so far, especially in the context of the recurrent representation, as it only looks back at previous states. Therefore, we need a way to create matrix A that can retain a longer memory, namely High-order Polynomial Projection Operators (HiPPO).

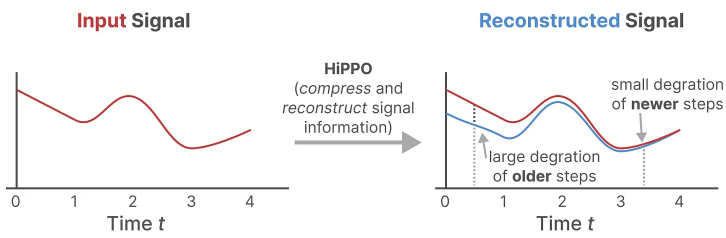

HiPPO attempts to compress all the input signals seen so far into a vector of coefficients.

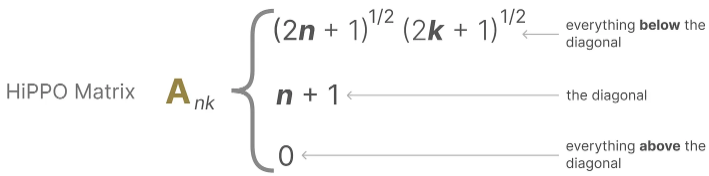

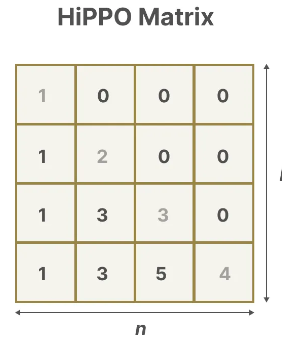

It uses matrix A to construct a state representation that captures recent tokens well and attenuates older tokens, producing an optimal solution for state matrix A through function approximation. The formula can be represented as follows:

As following table:

Building matrix A using HiPPO was shown to be much better than initializing it as a random matrix. As a result, it more accurately reconstructs newer signals (recent tokens) compared to older signals (initial tokens).

The idea behind the HiPPO Matrix is that it produces a hidden state that memorizes its history.

Mathematically, it does so by tracking the coefficients of a Legendre polynomial which allows it to approximate all of the previous history.

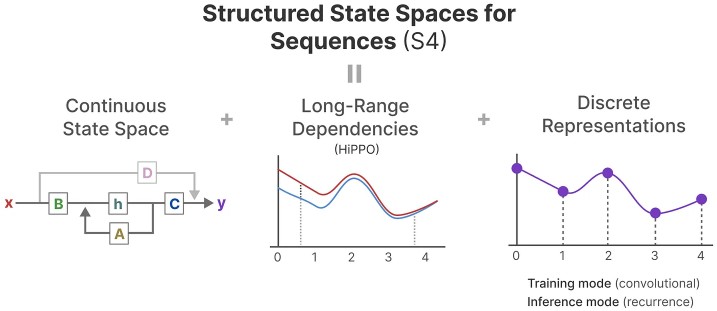

HiPPO was then applied to the recurrent and convolution representations that we saw before to handle long-range dependencies. The result was Structured State Space for Sequences (S4), a class of SSMs that can efficiently handle long sequences.

It consists of three parts:

State Space Models

HiPPO for handling long-range dependencies

Discretization for creating recurrent and convolution representations

This class of SSMs has several benefits depending on the representation you choose (recurrent vs. convolution). It can also handle long sequences of text and store memory efficiently by building upon the HiPPO matrix.

3 Mamba - A Selective SSM

We finally have covered all the fundamentals necessary to understand what makes Mamba special. State Space Models can be used to model textual sequences but still have a set of disadvantages we want to prevent.

In this section, we will go through Mamba’s two main contributions:

A selective scan algorithm, which allows the model to filter (ir)relevant information

A hardware-aware algorithm that allows for efficient storage of (intermediate) results through parallel scan, kernel fusion, and recomputation.

Together they create the selective SSM or S6 models which can be used, like self-attention, to create Mamba blocks.

Before exploring the two main contributions, let’s first explore why they are necessary.

3.1 What Problem does it attempt to Solve?a

State Space Models, and even the S4 (Structured State Space Model), perform poorly on certain tasks that are vital in language modeling and generation, namely the ability to focus on or ignore particular inputs.

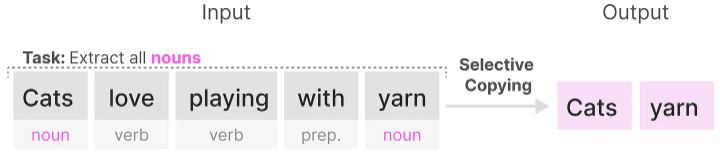

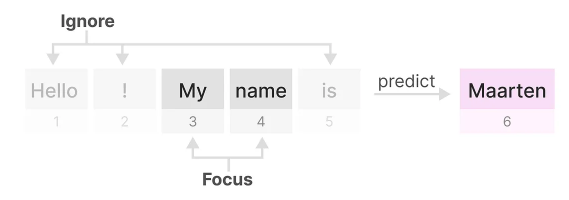

We can illustrate this with two synthetic tasks, namely selective copying and induction heads.

In the selective copying task, the goal of the SSM is to copy parts of the input and output them in order:

However, a (recurrent/convolutional) SSM performs poorly in this task since it is Linear Time Invariant. As we saw before, the matrices A, B, and C are the same for every token the SSM generates.

As a result, an SSM cannot perform content-aware reasoning since it treats each token equally as a result of the fixed A, B, and C matrices. This is a problem as we want the SSM to reason about the input (prompt).

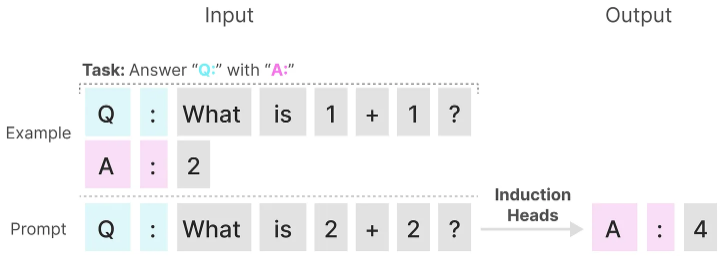

The second task an SSM performs poorly on is induction heads where the goal is to reproduce patterns found in the input:

In the above example, we are essentially performing one-shot prompting where we attempt to “teach” the model to provide an “A:” response after every “Q:”. However, since SSMs are time-invariant it cannot select which previous tokens to recall from its history.

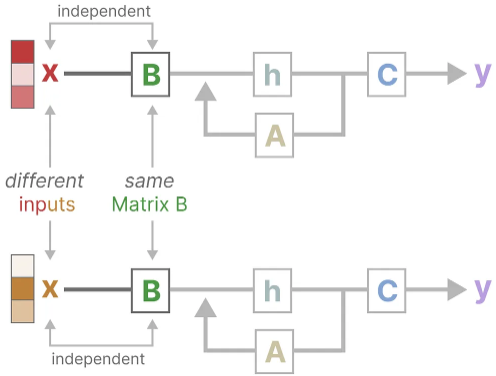

Let’s illustrate this by focusing on matrix B. Regardless of what the input x is, matrix B remains exactly the same and is therefore independent of x:

Likewise, A and C also remain fixed regardless of the input. This demonstrates the static nature of the SSMs we have seen thus far.

In comparison, these tasks are relatively easy for Transformers since they dynamically change their attention based on the input sequence. They can selectively “look” or “attend” at different parts of the sequence.

The poor performance of SSMs on these tasks illustrates the underlying problem with time-invariant SSMs, the static nature of matrices A, B, and C results in problems with content-awareness.

3.2 Selectively Retain Information

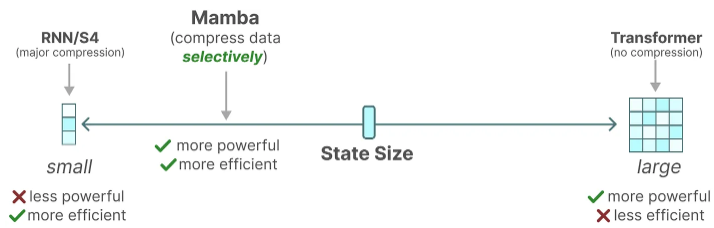

The recurrent representation of an SSM creates a small state that is quite efficient as it compresses the entire history. However, compared to a Transformer model which does no compression of the history (through the attention matrix), it is much less powerful.

Mamba aims to have the best of both worlds. A small state that is as powerful as the state of a Transformer:

As teased above, it does so by compressing data selectively into the state. When you have an input sentence, there is often information, like stop words, that does not have much meaning.

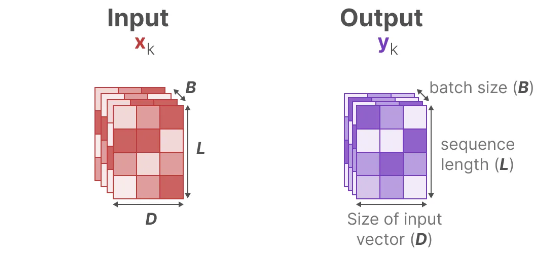

To selectively compress information, we need the parameters to be dependent on the input. To do so, let’s first explore the dimensions of the input and output in an SSM during training:

In a Structured State Space Model (S4), the matrices A, B, and C are independent of the input since their dimensions N and D are static and do not change.

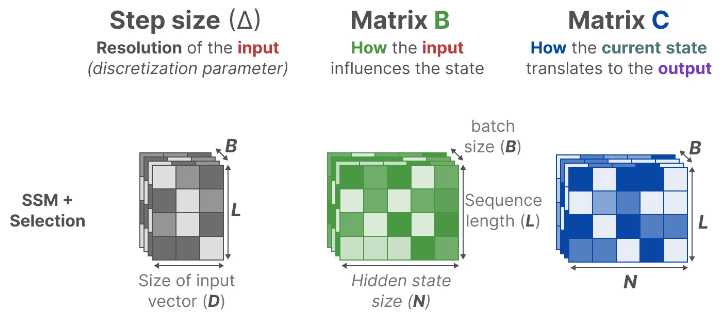

Instead, Mamba makes matrices B and C, and even the step size ∆, dependent on the input by incorporating the sequence length and batch size of the input:

This means that for every input token, we now have different B and C matrices which solves the problem with content-awareness!

Matrix A remains the same since we want the state itself to remain static but the way it is influenced (through B and C) to be dynamic.

Together, they selectively choose what to keep in the hidden state and what to ignore since they are now dependent on the input.

A smaller step size ∆ results in ignoring specific words and instead using the previous context more whilst a larger step size ∆ focuses on the input words more than the context:

3.3 The Scan Operation

Since these matrices are now dynamic, they cannot be calculated using the convolution representation since it assumes a fixed kernel. We can only use the recurrent representation and lose the parallelization the convolution provides.

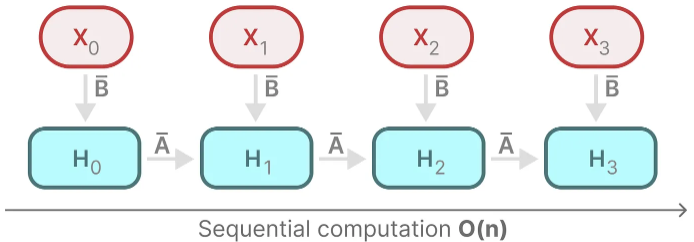

To enable parallelization, let’s explore how we compute the output with recurrency:

Each state is the sum of the previous state (multiplied by A) plus the current input (multiplied by B). This is called a scan operation and can easily be calculated with a for loop.

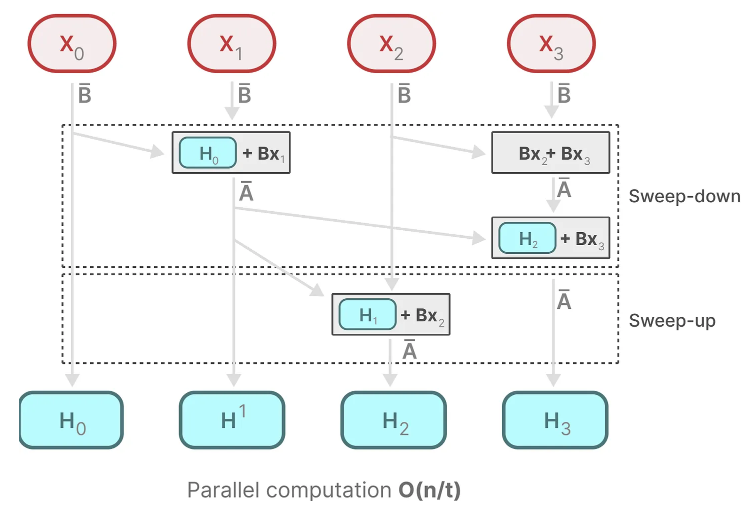

Parallelization, in contrast, seems impossible since each state can only be calculated if we have the previous state. Mamba, however, makes this possible through the parallel scan algorithm.

It assumes the order in which we do operations does not matter through the associate property. As a result, we can calculate the sequences in parts and iteratively combine them:

Together, dynamic matrices B and C, and the parallel scan algorithm create the selective scan algorithm to represent the dynamic and fast nature of using the recurrent representation.

3.4 Hardware-aware Algorithm

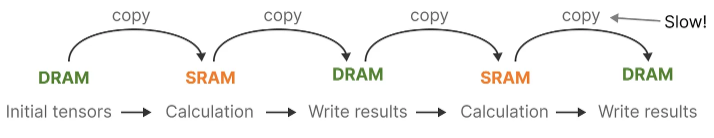

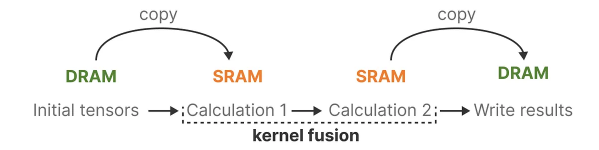

A disadvantage of recent GPUs is their limited transfer (IO) speed between their small but highly efficient SRAM and their large but slightly less efficient DRAM. Frequently copying information between SRAM and DRAM becomes a bottleneck.

Mamba, like Flash Attention, attempts to limit the number of times we need to go from DRAM to SRAM and vice versa. It does so through kernel fusion which allows the model to prevent writing intermediate results and continuously performing computations until it is done.

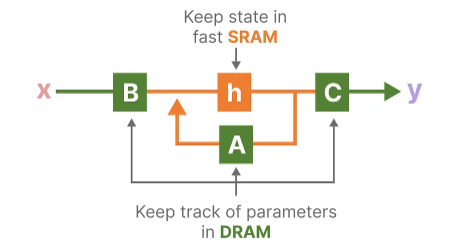

We can view the specific instances of DRAM and SRAM allocation by visualizing Mamba’s base architecture:

Here, the following are fused into one kernel:

Discretization step with step size ∆

Selective scan algorithm

Multiplication with C

The last piece of the hardware-aware algorithm is recomputation.

The intermediate states are not saved but are necessary for the backward pass to compute the gradients. Instead, the authors recompute those intermediate states during the backward pass.

Although this might seem inefficient, it is much less costly than reading all those intermediate states from the relatively slow DRAM.

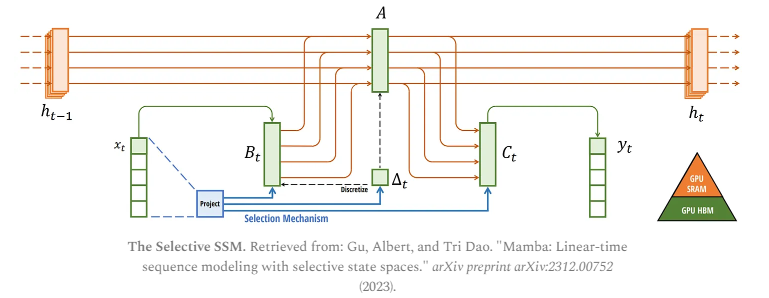

We have now covered all components of its architecture which is depicted using the following image from its article:

This architecture is often referred to as a selective SSM or S6 model since it is essentially an S4 model computed with the selective scan algorithm.

3.5 The Mamba Block

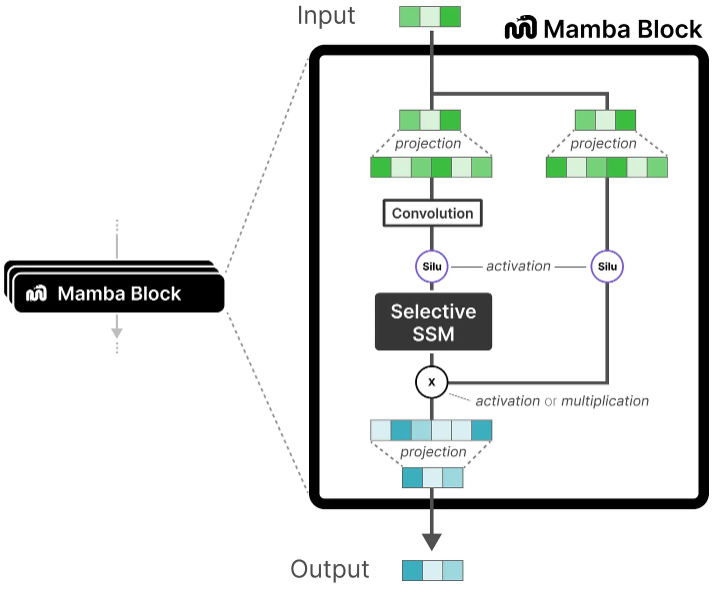

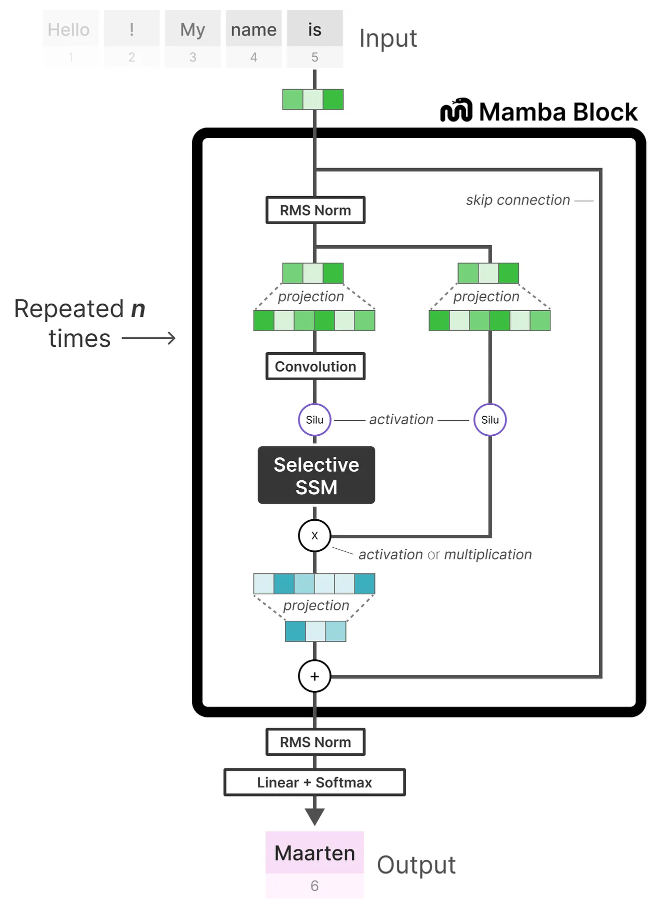

The selective SSM that we have explored thus far can be implemented as a block, the same way we can represent self-attention in a decoder block.

Like the decoder, we can stack multiple Mamba blocks and use their output as the input for the next Mamba block:

It starts with a linear projection to expand upon the input embeddings. Then, a convolution before the Selective SSM is applied to prevent independent token calculations.

The Selective SSM has the following properties:

Recurrent SSM created through discretization

HiPPO initialization on matrix A to capture long-range dependencies

Selective scan algorithm to selectively compress information

Hardware-aware algorithm to speed up computation

We can expand on this architecture a bit more when looking at the code implementation and explore how an end-to-end example would look like:

References and Resources:

A JAX implementation and guide through the S4 model: The Annotated S4

This video introducing Mamba by building it up through foundational papers.

Blog posts about the S4 models (blog1, blog2, blog3)

This blog post is a great next step to dive into more technical details about Mamba but still from an amazingly intuitive perspective.

Gu, Albert, and Tri Dao. “Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.00752 (2023).

Gu, Albert, et al. “Combining recurrent, convolutional, and continuous-time models with linear state space layers.” Advances in neural information processing systems 34 (2021): 572-585.

Gu, Albert, et al. “Hippo: Recurrent memory with optimal polynomial projections.” Advances in neural information processing systems 33 (2020): 1474-1487.

Voelker, Aaron, Ivana Kajić, and Chris Eliasmith. “Legendre memory units: Continuous-time representation in recurrent neural networks.” Advances in neural information processing systems 32 (2019).

Gu, Albert, Karan Goel, and Christopher Ré. “Efficiently modeling long sequences with structured state spaces.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.00396 (2021).