Extending Bio-Inspired DNNs To Colour Vision

Over the past decade, the monumental strides in artificial intelligence have been epitomized by the ascendance of deep neural networks (DNNs), which have set new benchmarks in a plethora of computer vision tasks—ranging from image classification to object detection and segmentation. Among these, Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (DCNNs) have distinguished themselves, not only for their superior performance but also for their brain-like computational patterns that mirror the gamma band activity in the human visual cortex (Kuzovkin et al., 2018). The architecture of these networks draws a remarkable parallel to the neural pathways of the mammalian visual system (LGN-V1-V2-V4-IT), enabling them to perform at or beyond human levels in various applications (Yamashita et al., 2018).

However, this technological vanguard is not without its imperfections. Recent studies have illuminated stark differences in how CNNs and human visual systems approach learning, with CNNs displaying a propensity towards texture over shape—contrary to earlier beliefs (Brachmann, Barth and Redies, 2017; Kubilius, Bracci and Beeck, 2016; Geirhos et al., 2019). This misalignment has profound implications, including vulnerabilities to adversarial attacks where deceptive modifications—imperceptible to humans—can fool these models into misclassifications (Goodfellow, Shlens and Szegedy, 2015).

Intriguingly, recent experiments reveal a dominant shape bias in human visual decision-making, present in up to 95.9% of trials (Geirhos et al., 2019), a trait that sharpens with age (Landau, Smith and Jones, 1988). In stark contrast, CNN models have exhibited a significant inclination towards texture, suggesting a foundational divergence from human perceptual processes (Malhotra, Evans and Bowers, 2020).

This divergence has spurred a vigorous debate on the optimal balance of training data diversity, which, while it dilutes performance, is critical in overcoming ingrained biases (Madan et al., 2022). Emerging from this discourse is ‘Ecoset’—a dataset closely aligned with human cognitive frameworks—which has shown promising results under representational similarity analysis (Mehrer et al., 2021).

Further innovation is evident in the application of biologically inspired filters at the DNN’s input layer, enhancing robustness and generalization capabilities without a substantial trade-off in accuracy (Evans, Malhotra and Bowers, 2022). These include the Difference of Gaussian and Gabor filters, the latter of which has been pivotal in addressing issues such as noise intolerance and bias amplification.

Moreover, while Gabor filters are adept at handling local contrast and discontinuities, they fall short in color discrimination—a limitation poised for breakthrough via the integration of a three-channel, colour opponency Gabor filter. This adaptation promises to refine the classification of color images significantly, leveraging the unique light and color sensitivity traits of the retinal ganglion cells (Hendry and Reid, 2000).

This ambitious project aims to explore the multifaceted effects of this advanced filter technology on DNN performance across varied scenarios, thereby shedding light on the intricate mechanisms underpinning these powerful computational models. The journey will traverse the extension of the Gabor filter to handle RGB channels, its validation against the human-centric Ecoset, and a comprehensive assessment of its impact on the robustness and generalization capabilities of DNNs.

Gabor Kernel

Early psychophysical experiments found that visual scenes were analysed in terms of independent spatial frequency channels (Campbell and Robson, 1968). This working mechanism is similar to some existing mathematical schemes, such as the Gabor method. The Gabor method has been used to approximate the distribution of single-cell receptive fields in mammalian cortex (Fleet and Jepson, 1993). Gabor filter is a commonly used linear filter in the field of image processing. It is a short-time windowed Fourier transform and has been widely used in image texture analysis (Marĉelja, 1980). Its impulse response is generated by multiplying a Gaussian envelope function with a complex oscillation, so in the two-dimensional state, relevant features can be extracted at different scales and directions in the frequency domain. Its equations contain real and imaginary parts representing orthogonal directions and can also be used alone as a complex number (Equation 1-4).

Complex-valued Gabor function: \(g(x,y) = \exp\left(-\frac{x'^2 + \gamma^2 y'^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \exp\left(i \left(\frac{2\pi x'}{\lambda} + \psi\right)\right) \tag{1}\)

Real part: \(g(x,y) = \exp\left(-\frac{x'^2 + \gamma^2 y'^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \cos\left(\frac{2\pi x'}{\lambda} + \psi\right) \tag{2}\)

Imaginary part: \(g(x,y) = \exp\left(-\frac{x'^2 + \gamma^2 y'^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \sin\left(\frac{2\pi x'}{\lambda} + \psi\right) \tag{3}\)

Coordinate transformation: \((x', y') = (x \cos \theta + y \sin \theta, -x \sin \theta + y \cos \theta) \tag{4}\)

where x and y specify the position of the light pulse in the field of view (Petkov and Kruizinga, 1997). θ represents the direction of the parallel strips in the Gabor filter kernel, and 0 is the vertical angle. γ is the spatial aspect ratio, which determines the ellipticity of the shape of the Gabor function. When γ=1, the shape is circular; when γ<1, the shape elongates with the direction of the parallel stripes. This value is usually 0.5. σ represents the bandwidth (standard deviation of the Gaussian factor), For larger bandwidth the envelope increase allowing more stripes and with small bandwidth the envelope tightens. The ψ function represents the phase shift of the sine wave function. Its value range is -180° to 180°. Among them, the equations corresponding to 0° and 180° are symmetrical with the origin, and the equations of -90° and 90° are centrosymmetric about the origin. λ represents the wavelength of the sine factor. Its value is specified in pixels, usually greater than or equal to 2, and usually less than 20% of the image size. However, we can use the parameter b to determine the value of λ, which represents the Gaussian envelope that describes the half-response spatial frequency bandwidth (the number of periods of the sinusoid) within. (see Equation 5).

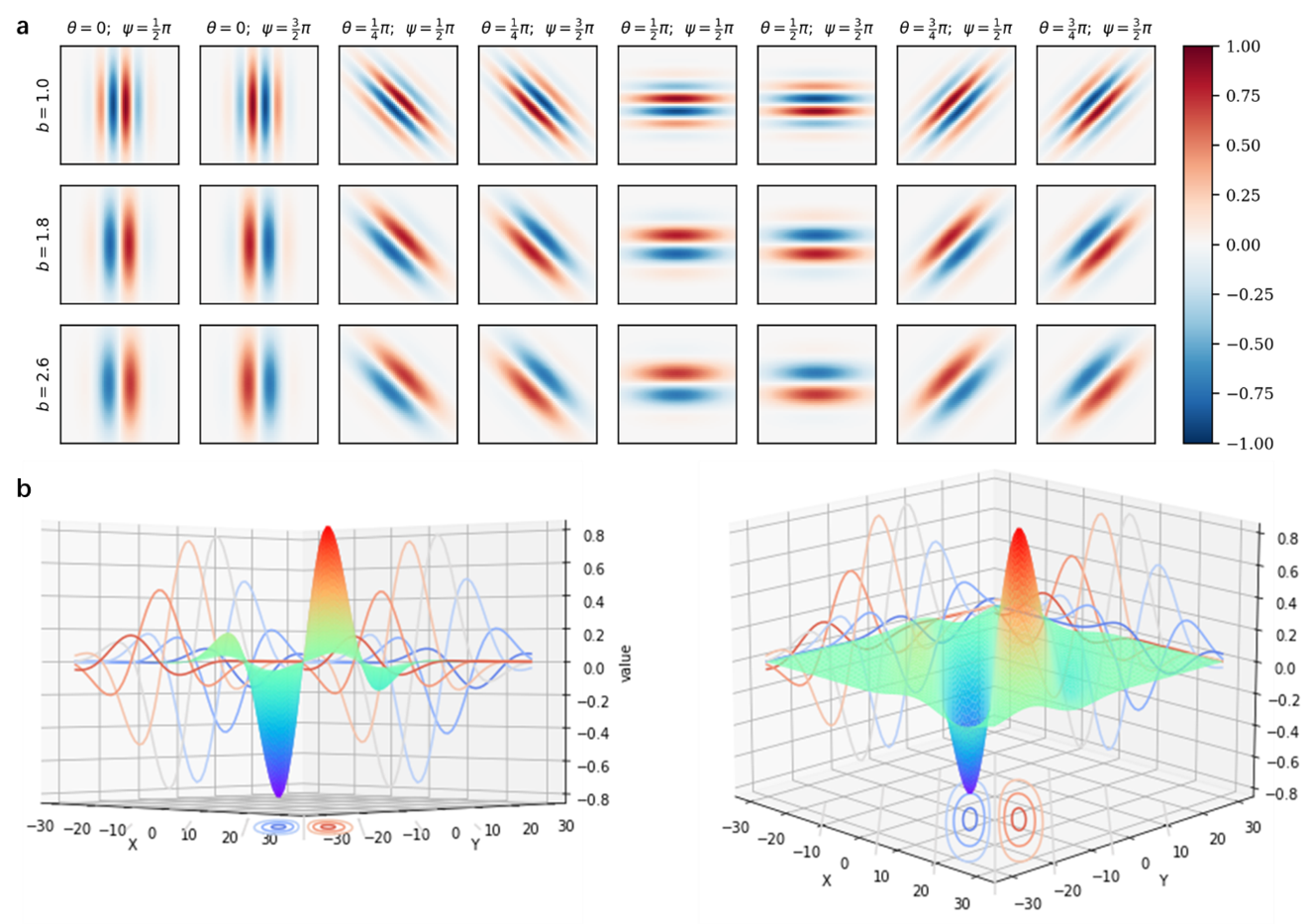

\[\lambda = \sigma \cdot \pi \cdot \sqrt{\frac{2}{\ln 2}} \cdot \frac{2^b - 1}{2^b + 1} \tag{5}\]In the initialized Gabor filter bank, the parameter selections in (table 1) were adopted in total, and the selections spanned the range matching the primate primary visual cortex (Petkov and Kruizinga, 1997). The visualization is shown in Figure, and 24 Gabor filter banks are generated according to the parameter combination of the table. kernel size is set to 31*31.

Colour opponency channels Gabor Filter

The retina is composed of three layers of neurons, the outermost being the photoreceptors, rods and cones, which for divariant colour vision are L and S cones. A second layer of bipolar cells transmits the signals of the photoreceptors to a third layer of neurons, the ganglion cells whose axons form the optic nerve (Gouras, 1995). Patterns of receptive fields in the retina as photoreceptors show spatial and chromatic antagonism. If one type of photoreceptors in the centre is excited by light stimulation, the opposite photoreceptors in the periphery are inhibited and vice versa. More than ten types of ganglion cells found in the early retina of primates show sensitivity to different light sources. Among them, Midget, parasol and bistratified ganglion cells account for about 90% of all ganglion cells found so far (Nassi and Callaway, 2009). Midget ganglion cells accounted for about 70% of the total cells projected to Lateral geniculate nucleus. Midget ganglion cells transmit red-green colour opposition, while bistratified ganglion cells transmit yellow-blue colour opposition, and the parasol ganglion cells transmit luminance. Through the above neurophysiological principles, we can model the retinal colour confrontation mechanism and extend it to the Gabor filter, thereby transforming the original digital signal into an analogue physiological signal that is more in line with neuroscience mechanisms. First we can define the luminance channel as I:

\[I = \frac{r + g + b}{3} \tag{6}\]where r, g, b represents the three colour channel matrices of the input image, respectively. Then we remodel the colour channel from the original colour channel based on the superposition principle of light:

Red component formula: \(R = \left\lfloor r - \frac{g + b}{2} \right\rfloor \tag{7}\)

Green component formula: \(G = \left\lfloor g - \frac{r + b}{2} \right\rfloor \tag{8}\)

Blue component formula: \(B = \left\lfloor b - \frac{r + g}{2} \right\rfloor \tag{9}\)

Yellow component formula: \(Y = \left\lfloor \frac{r + g}{2} - \frac{|r - g|}{2} - b \right\rfloor \tag{10}\)

where ⌊·⌋ represents half-wave rectification. We remove negative values from the matrix, the process is similar to the ReLu method. Then we extend the newly established colour channel to a colour opponency channel to simulate the working mechanism of Midget and bistratified ganglion cells.

We incorporated our innovative Gabor layer into the VGG and ResNet models respectively, and evaluated the model performance through rigorous testing. For both architectures, we utilized the stochastic gradient descent algorithm with a momentum of 0.9, conducting training over 200 epochs with a decay factor of 0.5 and a patience interval of 5 epochs. To optimize the convergence rate, we initialized the learning rate at 0.1 and set the batch size to 256. Traditionally employed in a 2D single-channel format, our study expanded the Gabor filter into a three-channel mirrored configuration, contrasting it with color-opposing Gabor kernels. The comparative analysis under the Cifar10 dataset is illustrated in the accompanying figure. Here, the single-channel Gabor filter on the VGG16 model achieved a 90% accuracy rate, albeit at a slight reduction compared to the VGG16 baseline. While the Gabor filter enhanced both robustness and generalization capabilities, this initial accuracy dip slightly diminished its practical applicability. However, transitioning to an RGB three-channel model substantially restored—and even marginally increased—this metric, benefiting from the enriched feature set of the tri-color channels. The color-opposed Gabor filters demonstrated superior outcomes, not only restoring but enhancing the model’s accuracy beyond its original levels.

The effectiveness of the Cifar-10 dataset is somewhat constrained by image resolution limitations, as low-resolution images do not capture extensive features, thereby capping potential accuracy enhancements. The Ecoset, with its diverse resolution range predominantly above 480p, aptly addresses this constraint and aligns closely with human cognitive processes. For consistent comparison, we standardized all images to a 32x32x3 format. The results, depicted in another figure, mirrored the findings from the Cifar10 assessment, with the accuracy of the OGVGG and OGResNet models still leading. Remarkably, the OGResNet reached an accuracy of 97.43%, and we noted a potential for further improvement as we managed to lower the learning rate during training. The uniform resizing of Ecoset images to 32x32 in our preprocessing likely led to a significant loss of feature detail. Nonetheless, extending the Gabor filter to three channels independently contributed to performance gains, illustrating that converting from a three-channel input to grayscale can strip away critical feature information.