Hybrid Time-Delayed and Uncertain Internally-Coupled Complex Networks

The human brain, a complex and dynamic network composed of billions of neurons linked by trillions of synapses, orchestrates a myriad of physiological and cognitive functions through intricate electrochemical signaling. To decipher its complexities, scientists utilize models such as the Neural Mass Model (NMM) and the concept of “Communication through Coherence” (CTC), which simplify the brain’s vast network into manageable ‘neural masses’ and emphasize synchronization and coherent oscillatory activities for effective information transfer. These models, while useful, may not capture the finer details of neural activity or network structures but provide foundational insights into brain dynamics such as synchronization, rhythm generation, and information propagation.

Moreover, the Kuramoto model, which describes the synchronization of large networks of oscillators through differential equations, complements these frameworks by offering a quantitative method to analyze brain network coherence and interactions between various brain regions. This model helps explore how these interactions affect cognitive states and functions, enhancing our understanding of the brain’s operational mechanics across different cognitive and behavioral states.

In an innovative approach, this study integrates real human brain data from Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI), Electroencephalography (EEG), and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) into the Neural Mass Model, extending it into a comprehensive Brain Mass Model (BMM). This integration not only enhances the model’s ability to simulate physiological characteristics but also aligns it with the Kuramoto model to observe electrophysiological signals and brain region synchronization simultaneously. This dynamic fitting of complex network models, supported by parallel fast heuristics algorithms, paves the way for more accurate simulations of brain dynamics, offering potential applications in understanding and treating various neurological conditions.

Real Human Brain Data Structure

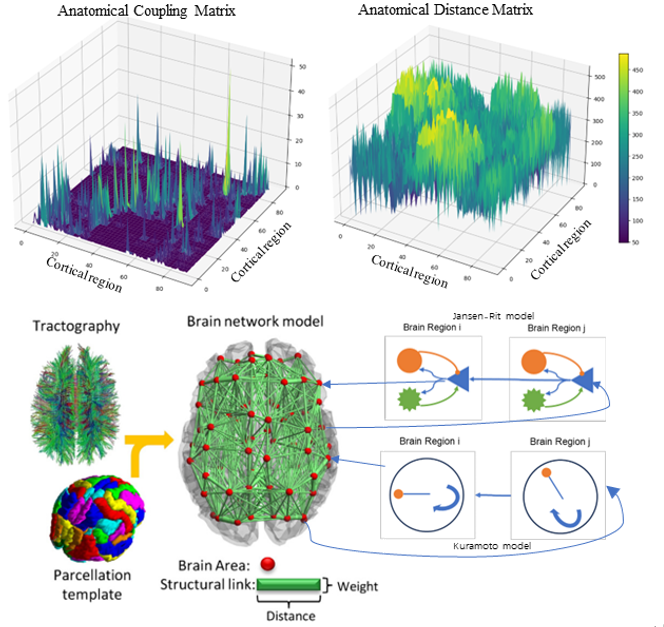

In the present study, the estimation of structural brain networks was based on Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) data, from Cabral’s (2014) research. All magnetic resonance scans were conducted on a 1.5 Tesla MRI scanner, utilizing a single-shot echo-planar imaging sequence to achieve comprehensive brain coverage and capture multiple non-linear diffusion gradient directions. To define the network nodes, the brain was parcellated into 90 distinct regions, guided by the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) template. Data preprocessing involved a series of corrections using the Fdt toolbox in the FSL software package ([26], FMRIB), aimed at rectifying image distortions induced by head motion and eddy currents. Probabilistic fiber tracking was executed using the probtrackx algorithm to estimate the fiber orientations within each voxel. For connectivity analysis, probabilistic tractography sampling was performed on fibers passing through each voxel. This data served as the basis for both voxel-level and region-level analyses. Connectivity between different brain regions was ascertained by calculating the proportion of fibers traversing each region.

Ultimately, two 90x90 matrices, C_ij and D_ij, were generated (see Fig. 1). C_ij characterizes the connectivity and strength of connections between brain regions, whereas D_ij represents the communicative distance between them. To normalize these matrices, all off-diagonal elements were divided by their mean value, setting the mean to one. D_ij was also subjected to normalization to adapt to a discrete-time framework. This was accomplished by dividing D by the mean of all values greater than zero in the C matrix, followed by scaling through a simulated unit time and subsequent integer rounding for direct matrix indexing. (Estimation is carried out based on the Euclidean distance between the centroids of the segmented regions.)

Extended Neural Mass Model with Coupling Strength and Time Delay

Neural Mass Models (NMMs) serve as mesoscopic mathematical frameworks de-signed to capture the dynamic behavior of brain regions or neuronal assemblies. Un-like models that simulate the activity of individual neurons, NMMs aim to under-stand the integrated behavior of neural systems at a higher level of abstraction [3, 4, 5]. They typically employ a set of differential equations to describe the interactions between different types of neuronal populations, such as excitatory and inhibitory neurons, and their responses to external inputs. These models have found extensive applications in the analysis of neuroimaging data, including Electroencephalography (EEG) and Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), as well as in simulating the dynamic expressions of neurological disorders like epilepsy and Parkinson’s disease.

One notable instantiation of NMMs is the Jansen-Rit Model (JRM), which has been frequently employed in past research to characterize specific large-scale brain rhythmic activities, such as Delta (1-4 Hz), Theta (4-8 Hz), and Alpha (8-12 Hz) waves. The JRM typically comprises three interconnected subsystems that represent pyramidal neurons, inhibitory interneurons, and excitatory interneurons. These subsystems are linked through a set of fixed connection weights and can receive one or multiple external inputs, often modeled as Gaussian white noise or specific stimulus signals. In previous research, the basic Jansen-Rit model has been extensively described, including structure, equations and parameter settings [19]. The JRM employs a set of nonlinear differential equations to describe the temporal evolution of the average membrane potentials within each subsystem, their interactions, and their responses to external inputs.

In the present study, we extend the foundational single JRM to a network-level system comprising multiple JRMs. Each node in this network communicates based on the AAL brain structure data described above, and a more vivid depiction can be found in Fig 1. Given that local circuits are now expanded into large-scale, brain-like network circuits, nodes need to receive signals emitted from other nodes. This inter-node communication is governed by a parameter K_ij, which reflects the connectivity across areas. Additionally, considering the influence of inter-regional distances on signal transmission, the signals between nodes are also modulated by a parameter τ_ij, which represents the unit time required for a signal to reach a designated node. As a result, we can extend the original equations to accommodate these additional factors.

\(\dot{y}_0^i(t) = y_3^i(t)\) \(\dot{y}_1^i(t) = y_4^i(t)\) \(\dot{y}_2^i(t) = y_5^i(t)\) \(\dot{y}_3^i(t) = G_e \eta_e S[y_1^i(t) - y_2^i(t)] - 2\eta_e y_3^i(t) - \eta_e^2 y_0^i(t)\) \(\dot{y}_4^i(t) = G_e \eta_e \left(p(t) + C_2 S[C_1 y_0^i(t)] + \sum_{j=1, j \neq i}^N K^{ij} x^j(t - \tau_D^{ij}) \right) - 2\eta_e y_4^i(t) - \eta_e^2 y_1^i(t)\) \(\dot{y}_5^i(t) = G_i \eta_i \left(C_4 S[C_3 y_0^i(t)]\right) - 2\eta_i y_5^i(t) - \eta_i^2 y_2^i(t)\)

Extended Kuramoto Model with Coupling Strength and Time Delay

The Kuramoto model serves as a mathematical framework for describing the collective behavior of coupled oscillators. Proposed by Yoshiki Kuramoto in 1975, the model aims to capture the spontaneous synchronization phenomena observed in groups of coupled oscillators [11]. In its basic form, the Kuramoto model describes N phase oscillators through the following set of ordinary differential equations:

\[\dot{\theta}_i = \omega_i + \frac{K}{N} \sum_{j=1}^N \sin(\theta_j - \theta_i)\]Here, (\theta) represents the phase of the oscillators, (\omega_i) denotes the natural frequency of the i^th oscillator, (N) is the total number of oscillators, and (K) signifies the coupling strength between the oscillators. When the value of (K) is sufficiently low, it implies that the oscillators within the subsystem are in a weakly coupled state, operating more or less independently. As (K) increases and reaches a critical value (K_c), the oscillators begin to exhibit synchronization. The coherence or order parameter of the Kuramoto model can be described using the following equation:

\[r e^{i \psi} = \left| \frac{1}{N} \sum_{j=1}^N e^{i \theta_j} \right|\]In this equation, (e^{i \theta_j}) is a complex number with a modulus of 1. The value of (r) ranges from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating a more synchronized system. To adapt the basic Kuramoto model to the current human brain network structure, the original equations can be reformulated as follows:

\[\dot{\theta}_i = \omega_i + K_{ij} \sum_{j=1}^N C_{ij} \sin(\theta_j(t-\tau_{ij}) - \theta_i(t))\]Given that the human brain network structure includes a matrix (C_{ij}) representing the connectivity between brain regions, the focus shifts to the influence between connectable network nodes. The global coupling parameter (K) is replaced by (K_{ij}), eliminating the need for averaging. In this context, the emphasis is on detecting the coherence between two specific oscillators (i) and (j), which can be calculated using the following equation within a time window (T):

\[r = \left| \frac{1}{T} \int_0^T e^{i(\theta_i(t) - \theta_j(t-\tau_{ij}))} \, dt \right|\]By adapting the Kuramoto model in this specialized context, the focus is shifted towards understanding the intricate relationships and synchronization phenomena between specific oscillators. This nuanced approach allows for the exploration of oscillator behavior in a more localized manner, contrasting with broader network models. It opens up avenues for investigating the subtleties of oscillator interactions, which could be particularly useful in specialized applications beyond the scope of traditional brain network models.